In 1985, I had an English teacher named Nick DiMarco. Mr. DiMarco rarely spoke, spoke quietly when he did, and accompanied moments of silence and speech with a look of anguished torment. Now that I am a mature adult who has completed more than one workplace personality assessment, I recognize Mr. DiMarco was an introvert whose quirks likely inspired fond admiration in people his age. But in 1985, I was a teenager assessing personalities with the guidance of Weird Al Yankovic, Saturday Night Live, and Mad Magazine. In my circle of friends, Mr. DiMarco’s quirks inspired jokes and snorts of laughter.

It was while flipping through a magazine and stumbling on a photo of a man who looked like Mr. DiMarco, tormented expression and all, that I decided to write a graphic short story about my English teacher. Inspired in the unhindered way of adolescence, I punctuated my prose with hand drawings and magazine cut outs that I glued to the page. A few hours later, I admired my work, eight sheets of satire thick with glue that I stapled together, titled The Nick DiMarco Story, and decided was clever enough to take to school the next day.

The Nick DiMarco Story made its way into English class where the hero himself sat at his desk at the front. During a quiet moment when we were supposed to be writing a haiku and Mr. DiMarco seemed safely distracted by a book, my classmates started passing around The Nick DiMarco Story. Two weeks earlier, this same group of students had successfully passed a twelve inch pizza and two-litre bottle of Coca Cola around a seventy-five minute French class under the nose of hard-of-seeing Madame Sirois. Eight pages of foolscap was nothing. However, Nick DiMarco was not Madame Sirois.

“Ha!” Derek Dupont guffawed as he finished the tale and reached across the aisle to pass it to Barb Wirvin in the desk beside him. Mr. DiMarco looked up from his book. His anguished gaze landed on Derek’s outstretched arm. Derek froze.

“Bring it here, Derek,” Mr. DiMarco said mildly.

My stomach sank. As he walked past my desk, Derek shot me a pitying look. He lay the pages on Mr. DiMarco’s desk before scurrying back to his own. I watched fearfully as the subject of my unfiltered humour put his book down, picked up The Nick DiMarco Story, and started reading.

Any hope of writing a haiku was obliterated by panic. Staring at the blank page on my desk, I recalled what I had written and groaned a little when I remembered the ending. “Stay tuned for the next adventure when Nick DiMarco goes grocery shopping, wonders why a carrot is called a carrot, and is stuck in Produce for days!”

When the bell rang, and everyone rushed for the door, Mr. DiMarco waved me to his desk. Looking up at me from his chair, he held the pages beyond my reach. I swallowed, waiting for the verbal execution.

“This is good,” said Mr. DiMarco.

Wait, what? I stared at him, not believing what I had heard.

“This,” he shook the pages for emphasis, “is a great piece of satire. Funny observations and visuals.”

He then thrust the story towards me, letting me grasp a corner of the pages.

“Next time,” he said before releasing it to my grip, “please share your extracurricular writing outside of class or ask for permission to share it in the class.”

Then, Mr. DiMarco did something I had not seen him do before. He smiled.

“Yes, sir,” I answered quietly, my cheeks burning with embarrassment.

Just as I started to think it would be safe to smile with him, his smile disappeared. He let go of the pages and dismissed me with, “That is all, Colleen.”

I never did write the next instalment of The Nick DiMarco Story. It was hard to satirize a man who could evaluate a joke made at his expense with objective curiosity. Clearly, Mr. DiMarco’s quiet torment was a sign of great character. I chose to retire the glue stick, point my pen at other topics, and avoid high school detention.

Oh, to be back in the days of mere high school detention!

In 2024, I live in a Canada where an online version of The Nick DiMarco Story could get me fines, house arrest, or jail. The Online Harms Bill is a piece of legislation peddled by our government as protecting kids from online exploitation. However, its clauses and provisions seem more bent on jailing ordinary Canadians for saying anything online that our government decides is “harmful.” What constitutes harm? It does not appear that the Bill knows. How do you prove harm? Not sure, but oh here is some direction. If a person feels there is harm. What could go wrong?

As a special treat for the financially strapped, the Bill sets up monetary rewards for anonymous “tips.” A ‘get-paid-to-snitch’ scheme we can tap into whenever we need a little grocery or gas money. Need a few dollars to fill the pantry for the in-law’s visit next week? Go find that tongue-in-cheek Facebook post from your neighbour and, presto! Prime rib and caviar!

“Orwellian,” declares Margaret Atwood.

“Poison,” warns Jordan Peterson.

“Unacceptable,” concludes the Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

And from everyday Canadians on X,

“Desperate,” cries dwiddlydo.

“See you in prison,” promises AEhronNulet.

Of course, the Bill might not be as “poisonous,” “unacceptable,” or “Orwellian” as it sounds. Perhaps the Digital Safety Committee, the group of five to six individuals the Bill decrees shall police us all, would never have time to scrutinize the online musings of regular Canadians. On the other hand, it is possible five people able to jail anyone who criticizes them might lose restraint and start wielding power like a fourteenth century monarch drunk on mead.

In fact, in January 2011, a similar-sized committee at the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council decided to act on a complaint from a single resident of St. John’s Newfoundland and ban Dire Straits’, Money for Nothing, from Canadian airwaves. Fewer people than can fit around my dining room table deprived thirty-seven million people of four minutes and six seconds of harmless radio joy or, if they were as offended as the lady in St John’s was, the burden of changing the station.

Yes, considering historical precedent in this country, many of us have good reason to believe we will see AEhronNulet in prison.

I imagine the entire Nick DiMarco Story affair would be different in future Canada with online harms and paid snitches. First, I suspect the contraband pizza and Coca Cola being passed around would be okay. It might even be encouraged, being a whim-satiating distraction from the nuisance of learning. Sure, an old dinosaur like Madame Sirois might tell students to save the food for lunchtime, but one yowling protest of colonialist pizza-phobia (“Ways of eating!”) would put an end to that. The teacher would probably slump into a bean bag, grab a slice, and start a movie.

Eight pages of sharp wit, however. That would be a different story.

Before English class had even begun, I imagine one or two of these future classmates would have read The Nick DiMarco story on Substack, immediately recognized the opportunity for easy pizza money, and sharpened their cry-victim pitchforks. While I wrote a haiku about the sunrise, they would use the Digital Safety App to tip off the Committee and watch rewards appear in their bank accounts. In seconds, artificial intelligence would take over and authorities would be notified.

Derek Dupont would not be in the classroom that day. With a sense of humour that made girls laugh and could have won him a full-time spot on Saturday Night Live in 1985, Derek would have inspired jealousy in a shyer and more awkward boy in future ‘no-harm-allowed-but-don’t-ask-us-what-harm-is’ Canada. The boy would only need to say he suspected Derek would post something harmful to Snapchat and Derek would be in an ankle monitor, under house arrest, and out of the running for a date to the prom.

Come to think of it, Barb Wirvin would not be in class either. Ever, I imagine. “What an idiot!” Barb was known to exclaim loudly when confronted with people who acted like idiots. Transplant that to Facebook, and there would surely be a teacher claiming emotional trauma and pleading with the Committee to stop being soft with five thousand dollar fines and slap Barb with that life imprisonment The Online Harms Bill promises.

In fact, ankle monitors would become common, a sign that some students were true rebels, to be feared and revered. Instead of huddling in the parking lot to smoke, the ankle monitor kids would lurch through the quad, swinging one leg awkwardly, careful not to breach the school’s perimeter and the confines of their imprisonment, but coming just close enough to prove their spirits were not completely broken.

Before I could put the finishing touches on the sunrise haiku, the principal would poke her head into our English classroom and ask Mr. DiMarco if she could “borrow Colleen for a moment.”

“Bring your things, dear,” she would say sweetly with an expression like cold stone.

Students already giggling at the story would screw up their faces, bite their tongues, and swallow their laughter, terrified of who might be firing up their smartphone to report the giggling and a future harm.

I would have little choice but to pack up my books and head for the door to face my fate. Hearing someone behind me, I would turn and see Mr. DiMarco holding his phone in one hand and swinging his bag over his shoulder with the other.

“This,” he would shake the phone for emphasis, “is a great piece of satire. I shared it on Facebook.”

Then, shooting his look of anguished torment at the Anti-Harm Police now crowding the classroom door, he would lurch past me, swinging one leg awkwardly.

This is when I would feel a surge of hope, when I would realize that an Online Harms Bill was no match for the human spirit, that the darkness would never consume the light, and that no matter how hard they try, five people would never stop enough of the thirty-seven million to stamp out the human quest for truth.

Because this is when I would look down and see Mr. DiMarco’s ankle monitor.

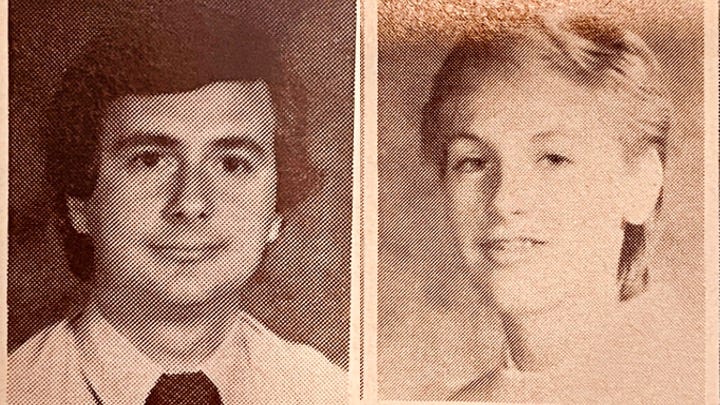

The author and Nick DiMarco in 1985. They even look like mug shots.

Share this post